On the Road: Early Live Moog Modular Artists

This is the first of a series of blogs on early live uses of the Moog Modular. Before Keith Emerson took his mammoth “Monster Moog” on tour in 1971 (an astonishing feat by any measure) there were several forays into live performances by a number of Moog users. Their experience spanned music genres, from classical, experimental, art rock, and jazz. All before the year 1970.

For a little perspective, lets remind ourselves about the Moog that Emerson used in live performances of Emerson, Lake & Palmer. Along with his other keyboards (Hammond organ, grand piano, etc.) he brought a fully-outfitted Moog Modular. The Moog unit alone weighed an overwhelming 550 pounds, stood ten feet tall, and required four roadies to transport and setup. (1) It was a magnificent monument to the lavishness of progressive rock.

Beginnings

Bob Moog originally designed the Moog Modular synthesizer to meet the specifications of musician Herb Deutsch. Over time, it became a kind of replacement for the disconnected contraptions traditionally found in the tape composition studio. He packaged many of the functions found in studios into the modules of his synthesizer, including reverb, filters, envelope generators and a sequencer for automating the laborious task of editing music sequences. The fact that he also bundled studio-sized tape recorders and an audio mixer into the purchase was by no accident. For example, when I arrived at the electronic music studio at Temple University in 1971, it comprised equipment provided solely through Moog. The same upgrade was being made at colleges across the country, replacing a hodge-podge of sound generating and recording equipment with one reliable platform that was all interconnected.

But the very idea of setting up a Moog Modular for live performance was present as early as 1964. The first two units purchased, even though not used live in front of an audience, look as though they could have been. They weighed about 115 pounds–the keyboard alone was about 25 lbs. not an insurmountable weight for musicians accustomed to traveling with Hammond organs and sound systems. Several artists felt that electronic music was best experienced live, performed in real-time, rather than using a previously-made recording as was the practice in much classical music. The Moog Modular units offered during the late sixties all had the potential of being used live on stage. But only a brave few took the risk of making this happen.

John Mills-Cockell

One story about the early Moog seems to have gone unnoticed by many. It comes from Toronto where a quartet of experimental artists purchased a modular unit from Bob Moog and used it in live performance several times. I have been in touch with John Mills-Cockell, who was a member of the experimental multimedia group Intersystems in Toronto. “In late 1967,” explains Cockell, “we began communications with Robert Moog in Trumansburg. It was a six-hour drive from Toronto and I made the trip several times as we figured which system we wanted. Of course it was a hefty financial outlay for us at that time, but we were determined that it was to be part of the artistic arsenal of our collective.” Intersystems was an experimental arts collective that included Blake Parker, Mills-Cockell, Dik Zander, and Michael Hayden. “I had been working with electronic sound for a few years at this point,” says Mills-Cockell, “and the idea of a modular, patchable all electronic instrument that could be played using a keyboard seemed like a dream come true.” They also acquired a Bode Ring Modulator and a filter from Moog.

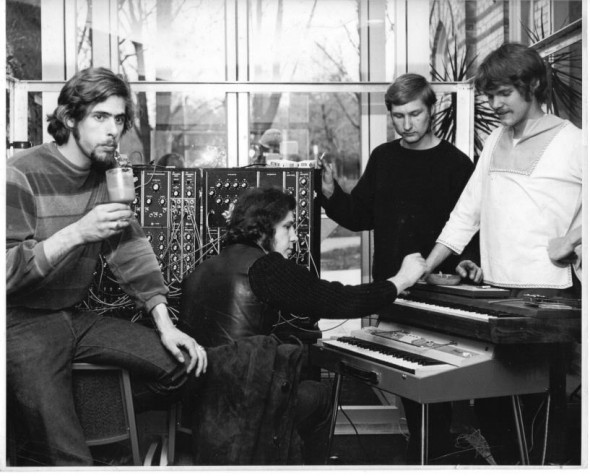

Intersystems, circa 1968. From left, Blake Parker, John Mills-Cockell, Dik Zander, Michael Hayden. Showing a Moog Modular synthesizer IIP with its keyboard and ribbon controller sitting on top of a Vox organ.

Duplex was one of the pieces performed by Intersystems. John describes the work and provides some insight as to one approach for working with the Moog Modular in real-time:

“The piece we performed was based on poems of [Blake] Parker accompanied by electronic music using the Moog and a few other instruments such as the Vox organ. At that time the music was primarily improvised, structured by a few simple themes and motifs, and the specific synth patches I created for the piece. These were modified, rematched in real time during the course of the performance, but essentially Duplex was performed as a non-stop continuum, about an hour in duration. Blake [Parker’s] poetry at the time was strongly influenced by William Burroughs, dada and the beat poets, but he always had a distinctive voice.”

Intersystems released three albums in two years, all of which are extremely hard to find. John described the Moog connection of each:

Number One (1967): “Pre-Moog, using a variety of homemade electronic devices and acoustic instruments.”

Peachy (1967): “Intersystems was the first recording we made using the Moog. It is interesting to note, I think, that I employed a hybrid compositional approach using musique concrete techniques (cutting up 1/4″ tape recordings of the Moog and reassembling them using chance procedures), real-time improvisation, and conventional music themes using standard equally tempered scales, admittedly approximate. I spent a lot of time trying to keep the Moog in tune using the voltage controlled keyboard, but I also made much use of the ribbon controller. I also imported a couple of recordings of brief snippets from radio broadcasts. Blake Parkers poems were somewhat similarly restructured, consisting of a short narrative, retold several times loosely using a kind of variations approach.” Listen to the track, “Peachy” here:

Free Psychedelic Poster Inside (1968): “More conventional in some ways, because each piece is a discrete, continuous composition/improvisation based entirely on the Moog Mark II supplemented occasionally by the electronic organ. The narrative is rather like a téléroman, a soap opera as it were.” Listen to “Part 9” of this album:

Mills-Cockell and Blake Parker worked closely on all three albums. Although the music was improvised, it was somewhat predetermined by the Moog patches, other instruments, and scripted poetry. “The electronic scores & poetry were quite careful choreographed as entities,” explained Mills-Cockell.

At the end of 2015, the record label Alga Marghen of Milan (Alga Marghen 37NMN 093LP) worked with Mills-Cockell to reissue the three Intersystems records with a 125-page book chronicling their work.

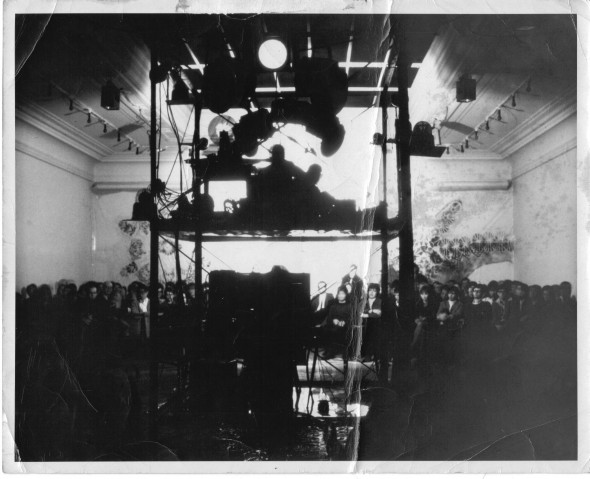

Which bring us to live performances. Intersystems was very much about performing their material for audiences. One of their first performances with the Moog took place in Toronto on March 6, 7, and 8th, 1968 at the Art gallery of Ontario (see photo). This was presentation of Duplex and the photo shows the structure which housed Blake and Mill-Cockell on the bottom with Zander and Hayden with projectors, color wheels and other paraphernalia on top. “Our show coincided incidentally with the famous chess match between John Cage and Marcel Duchamp at Ryerson Polytech (now University),” explains Mills-Cockell. “However we had good sized audiences every night.”

Intersystems Duplex Presentation, Art Gallery of Ontario, March 1968. Parker and Mills-Cockell (with Moog) were housed in the bottom structure; Zander and Hayden were stationed on top with projectors, color wheels, and other light show materials.

Following Intersystems, Mills-Cockell went on to perform with the Moog as a guest of the rock group Kensington Market on March 22, 1969 at Toronto’s Rockpile festival. During 1970 he was a key member of the progressive band Syrinx and used the Moog on one album before they lost it in a fire.

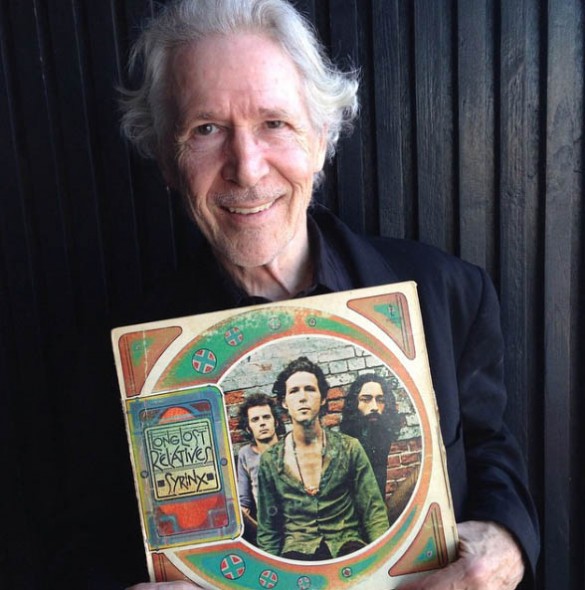

Mills-Cockell went on to a distinguished career as a composer, musician, and sound designer. He has created scores for Vancouver Playhouse, The National Arts Centre, Firehall Arts Centre, Citadel Theatre, Glasgow Museum of Art, and Phoenix Theatre. He is pictured here in a recent photo sporting an old Syrinx LP.

Many thanks to John Mills-Cockell for revealing a Toronto Moog connection that is not very well known. He and Intersystems had a devotion to making live electronic music that was shared by few others at the time. The wonderfully experimental Intersystems tracks that are available again through the new Alga Marghen release document an important period of musical experimentation that shouldn’t be forgotten.

(1)Bernstein, David , “A Comeback for Another Classic Rocker: The Moog Synthesizer”, The New York Times, September 29, 2004

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

Twitter: @Thom_Holmes

blog: Noise and Notations

If you want to read more from Thom Holmes, please see his many fascinating historical blogs here: http://moogfoundation.

Great article… I just ran to amazon to pick up the recordings released by the Alga Marghen label! Thanks for the tip!

Hi,

Just wondering if you were aware of Ruth White’s contribution to electronic music, as I didn’t see anything in your article. She was an early pioneer. I added a website just for your information.

All the best

I have that excellent Syrinx album. They did produce at least a second album as well, and I’m pretty sure it had the Moog on it as well, though it may have been another unit after the fire.

Interesting to note that what drew me to Syrinx’s music was that one of their musical pieces from the album in Mr. Cockell’s hands was the theme song to a fantastic TV show called “Here Come the Seventies”, which for its time was an excellent view into the exciting world of technological and social innovation which seemed to be very much in its heyday. Great piece – synth, synthesized drums, Mr. Pringle’s saxophone played through a wah-wah pedal or similar variable filter.

What with Canada (Montreal specifically) being the center of the world (temporarily) thanks to Expo 67 and Man and His World in ’68, these were exciting times and a lot of innovative music and other forms of art were really flourishing in Canada… almost 50 years ago now.

Wow, Holmes looks just like Mills-Cockell ;D