Not-a-Moog: Early Recordings Often Mistaken for a Moog (and Other Intriguing Cases)

Last month, I offered a list of the very first ten commercial recordings to feature the Moog Modular Synthesizer. There are numerous other recordings from this same time frame that occasionally get mentioned as including a Moog. However, I dont think they do. The reason for this confusion is pretty simple. Unless one knows what to listen for, the sound of the Moog might be confused with other electronic keyboard instruments or studio effects and tape tricks. Here is a rundown and the history of these prime suspects.

Maurice Jarre, Doctor Zhivago soundtrack

(LP, MGM Records S1E-6ST, January 13, 1966)

The possible granddaddy of all early Moog records is this movie soundtrack. If only one could hear the Moog! With such audible evidence, this recording would clearly be the first to feature a Moog, and by more than a year. Composer Jarre claimed that he used a Moog on this record, the sessions for which were in the Fall of 1965. An early Moog Modular model was available at the time, but even more importantly, early Moogist Paul Beaver was at the center of Jarre’s account of these sessions. Beaver would likely have been the only available musician to make a Moog session possible in Los Angeles at that time. But in Jarre’s own words, the electronic music in Doctor Zhivago is actually mixed deep into the score to add another dimension, not used as blatantly as the synthesized music of today. Using a synthesizer was uncommon at that time. [i] So, while Jarre’s account is most certainly accurate, Ive listened to the vinyl soundtrack release (the extended, two-disc version) many times and cannot detect a single obvious Moog sound. That’s not to say that there isn’t a Moog buried in the mix, but if you can’t hear it–and the instrument is uncredited in the liner notes–then such a recording clearly cannot be listed as an influential early Moog release.

The Ventures, Strawberry Fields Forever B/W Endless Dream

(single, Liberty 55967, May 6, 1967)

This is another rumored Moog record. If it were, it would also be among the first ten Moog recordings. But I’m not convinced. Paul Beaver is credited by at least one source as having played on the cover version of Strawberry Fields Forever.[ii]

I’ve listened to this many times and as interesting as it is, I cannot hear a sound that couldn’t have been made by other studio tricks or instruments (echo, tape reversal, reverb, slide guitar, distortion). The track also features electronic piano, organ, and an electric sitar. It is taken from the album Super Psychedelics, a spectacular instrumental album by the kings of surf guitar, but without Moog.

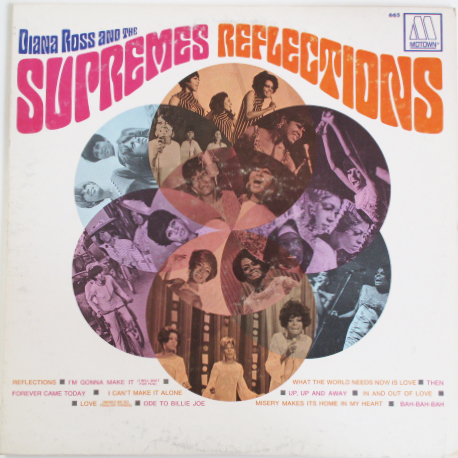

The Supremes, Reflections B/W Going Down for the Third Time

(single, Motown 1111, August 12, 1967)

This recording of Reflections is the most often cited case of a misidentified early Moog. It is often thought that the sliding electronic tone first heard in the opening of this song was made using a Moog. Motown did indeed purchase a Moog, but not until four months after this record was released. Motown engineer Bob Olhsson recently told me, in fact, that no Moog was used on this song. The tone in question was, in his words, an Eico audio oscillator with the engineer wailing on the dial.[iii] The song Forever Came Today, released as a single and found on the Reflections album (both in March 1968), featured what sounds like the same Eico oscillator, not the Motown Moog. The case of Motown points out a general law of Moog use on early recordings: The justification for using a Moog was inversely proportional to the ability to create a similar sound by simpler means.

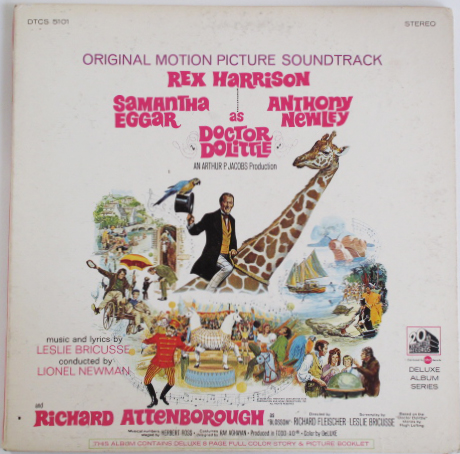

Doctor Doolittle soundtrack

(LP, 20th Century Fox Records DTCS 5101, September 16, 1967)

Moog programmed by Paul Beaver. Bernie Krause told me that Paul Beaver worked on this one. He provided uncredited Moog Modular music for the soundtrack.[iv] I have not been able to detect any obvious Moog music or sounds on the soundtrack LP, so his contribution may be limited to the motion picture itself. Accordingly, one can’t call this a Moog recording.

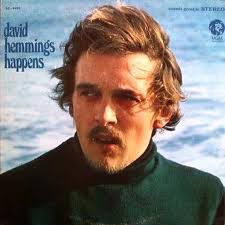

David Hemmings, Happens

(LP, MGM SE 4490, October 7, 1967)

This album of folkie raga rock by British actor David Hemmings was made with many of his Los Angeles friends, including Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, who purchased a Moog the following year. The original album had no credits and the reissue does not mention a Moog. Nor do I hear one. Keyboard instruments I do hear include electric harpsichord, combo organ, and probably an Ondioline.

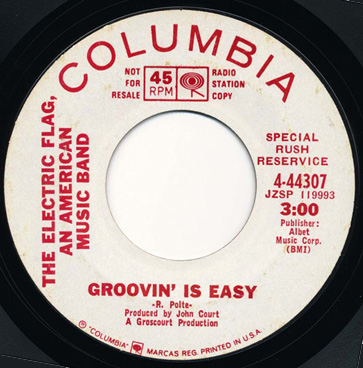

The Electric Flag, Groovin is Easy B/W Over Lovin You

(single, Columbia 4-44307, October 28, 1967)

This was a single release from the album A Long Time Comin’, (March 1968) by The Electric Flag, one of the first rock groups to record with a Moog. Paul Beaver worked on that album, and although there are some suspicious Moog-like tones on “Groovin is Easy”, they were more likely made with a flute or recorder, which would have been much easier to do than trying to patch-up a synthesized flute sound not heard anywhere else on the album. I do not hear a Moog on the B-side either.

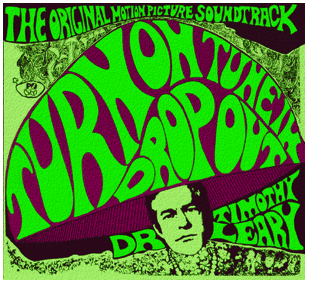

Timothy Leary, Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out

(LP, Mercury Records 21131, November 25, 1967)

This is the soundtrack for a documentary film made with LSD guru Dr. Timothy Leary. The film consisted of five short, experimental vignettes. Most of the music on this soundtrack consisted of reverberating sitar, guitar, banging gongs, and Leary’s soft lecturing voice, suggestive of a Yoga instructor. The electronic sounds heard on this album do not consist of signature Moog effects and could have been produced using tape composition techniques and simple electronic signal generators. There are credits for musicians, but not for anyone playing a Moog. I’m still researching this recording but for now I must put it in the Not-a-Moog category.

101 Strings, Astro-Sounds From Beyond the Year 2000

(LP, Alshire S-5110, 1969)

The 101 Strings was the name given to a long series of easy listening albums released by budget label Alshire Records in the 1960s and 1970s. They specialized in cover versions of popular songs, arranged for string orchestra and rhythm section. They produced dozens of albums, often orbiting around a theme such as songs by a particular composer (Cole Porter, Richard Rodgers, etc.) to less intelligible concepts such as Songs of the Seasons in Japan. Astro-Sounds From Beyond the Year 2000 was intended to capitalize on psychedelia by remixing some basic rock tracks that Alshire had already released in 1967. The instrumentals were first recorded by a group of studio rock musicians calling themselves The Animated Egg (Alshire 5104), led by session guitar player Jerry Cole. For this release in 1969, the same tracks were given various electronic treatments, such as phasing, distortion, reverberation and a full string section. Rumored to have a Moog, it has none.

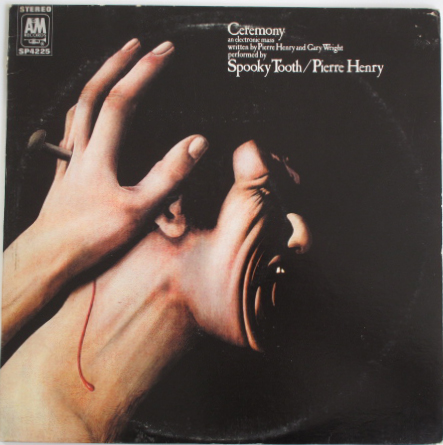

Spooky Tooth/Pierre Henry, Ceremony, An Electronic Mass

(Island Records ILPS 9107, December 1969, UK; A&M SP4225, May, 1970, US)

Depending on your point of view, this was either one of the greatest missteps in early progressive rock or a fantastically original album that was way ahead of its time. Whichever the case, most people can agree that it was the first step in the demise of Spooky Tooth. This concept album combined some basic rock tracks written around a religious theme by Gary Wright with electronic music composed by legendary French electronic music composer Pierre Henry. Henry’s contribution was so striking that a listener unfamiliar with musique concrete (the school of classic French tape music techniques) had trouble digesting the spasmodic and disconnected clatters of tape loops and modified natural sounds that Henry laid all over the rock tracks. The only electronic keyboard instrument present is Wright’s magnificent Hammond organ. All of the other sounds were made using classic tape editing techniques without the benefit of a Moog Synthesizer. What confuses this matter today is that online music catalogs such as AllMusic often credit the presence of any type of electronic keyboard with the generic term synthesizer, even if they mean organ.

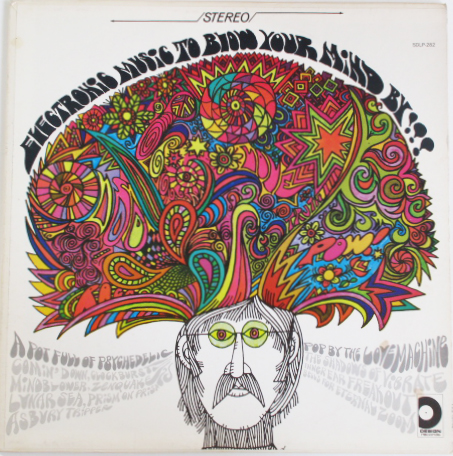

The Love Machine, Electronic Music to Blow Your Mind By!

(Design Records SDLP-282, 1967)

There are no credits on the record. Just a freaky cover and a generic back cover from this label known for mass-producing pop music and cover versions. The liner notes read, in part, “Design has created a series of Family Favorites covering everything from When the Saints Go Marching In to the Beethoven Fifth Symphony .” Low-cost recordings of familiar favorites by outstanding popular, Broadway, semi-classical and classical artists. This is actually a pretty interesting album combining tape effects with various musical instruments such as an organ, tons of reverb, echo, and a simple audio oscillator.

Brotherhood, Joyride, Friend Sound

(RCA, LSP-4114, 1969)

This is the second project by the group Brotherhood, whose 1968 self-titled album (RCA LSP 4092) featured some Moog Modular sounds. For that session, the group hadn’t intended to use the synthesizer at all, but Bob Moog was visiting the RCA studio in Hollywood and had set up a demonstration of the synthesizer. Bob asked them to try it out and the band used it on two tracks, ”Jump Out the Window” and “Forever”, all programmed by Bob himself. It is often assumed that the group used the Moog on this second album, Joyride, Friend Sound, but thats not the case. The record includes a lot of interesting sound collages and effects, but they are all done using standard studio techniques. The Moog is not mentioned in the liner notes but there are credits for Control console effects (Drake Levin, Michael Smith, Jim Valentine) and organ.

So, while these albums are sometimes confused with recordings of the Moog, they are still a lot of fun to listen to. Recordings from this period represented an interesting transition in the use of electronic sounds, from the traditional way of crafting them to the introduction of synthesizers

To read the first installment of this blog series exploring how technology and musical artistry influence one another, click here.

To read the second installment of this blog series with the first 10 recordings using a Moog, click here.

***All images provided by Thom Holmes

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

Twitter: Thom_Holmes

blog: Noise and Notations

http://www.thomholmes.com/

If you want to read more from Thom Holmes, please see his many fascinating historical blogs here: http://moogfoundation.

[i] From Maurice Jarre’s liner notes to the 30th anniversary edition of the soundtrack to “Dr. Zhivago.”

[ii] Del Halterman . Walk-Don’t Run – The Story of The Ventures, 2008, p. 382.

[iii] Bob Olhsson, personal correspondence.

[iv] Bernie Krause, personal correspondence.

Cool… I bet that must have been a Moog that terrified me as a child ~ those eerie ambient winds, noise and scary clanging sounds in Yuri’s mother’s funeral piece in the Dr. Zhivago soundtrack!

How about Bill Purcell’s Our Winter Love? I believe a distorted bass guitar and saxophone were used to produce the Moog-like sounds on that piece.