Dick Hyman (b. 1927) was already on his way to becoming a musical legend by 1968, and it had nothing to do with the Moog modular synthesizer. Having established himself as a jazz and studio keyboardist, arranger, and composer, he found himself thrust into yet another role — that of pioneering electronic musician.

At the time, Hyman was extremely busy as a session musician for Enoch Light’s Command label, known for its adventurous recordings of instrumental music and exotic arrangements. Hyman’s New York recording sessions for Command and other companies kept him busy for many years as a pianist, organist, arranger, and occasional player, as needed, of other keyboards.

Then along came Bob Moog’s synthesizer.

When producer Enoch Light (1905-78) heard the Moog, he knew that it had to become a part of the new sound of Command Records. Before long, Light had the most remarkable keyboard player in his organization sitting in front of the Moog to see what would happen, and the results are now part of recorded music history.

For this edition of the blog, Dick Hyman helped me look back at his remarkable recordings with the Moog modular synthesizer.

Many early Moog experimenters viewed the synthesizer primarily as a special effects machine. But Hyman, like a select few of his contemporaries including Carlos, Kingsley, Beaver, Krause, and Perrey, recognized the musical potential of this instrument.

Even though the synthesizer resembled, in Dick’s words, “a telephone switchboard,” he quickly grasped the unique tonalities that one could coax from it. As a session musician who spent an enormous amount of time recording in a multi-track environment, Hyman already had the mindset and patience to build interesting music, track by track, using the Moog’s monophonic output.

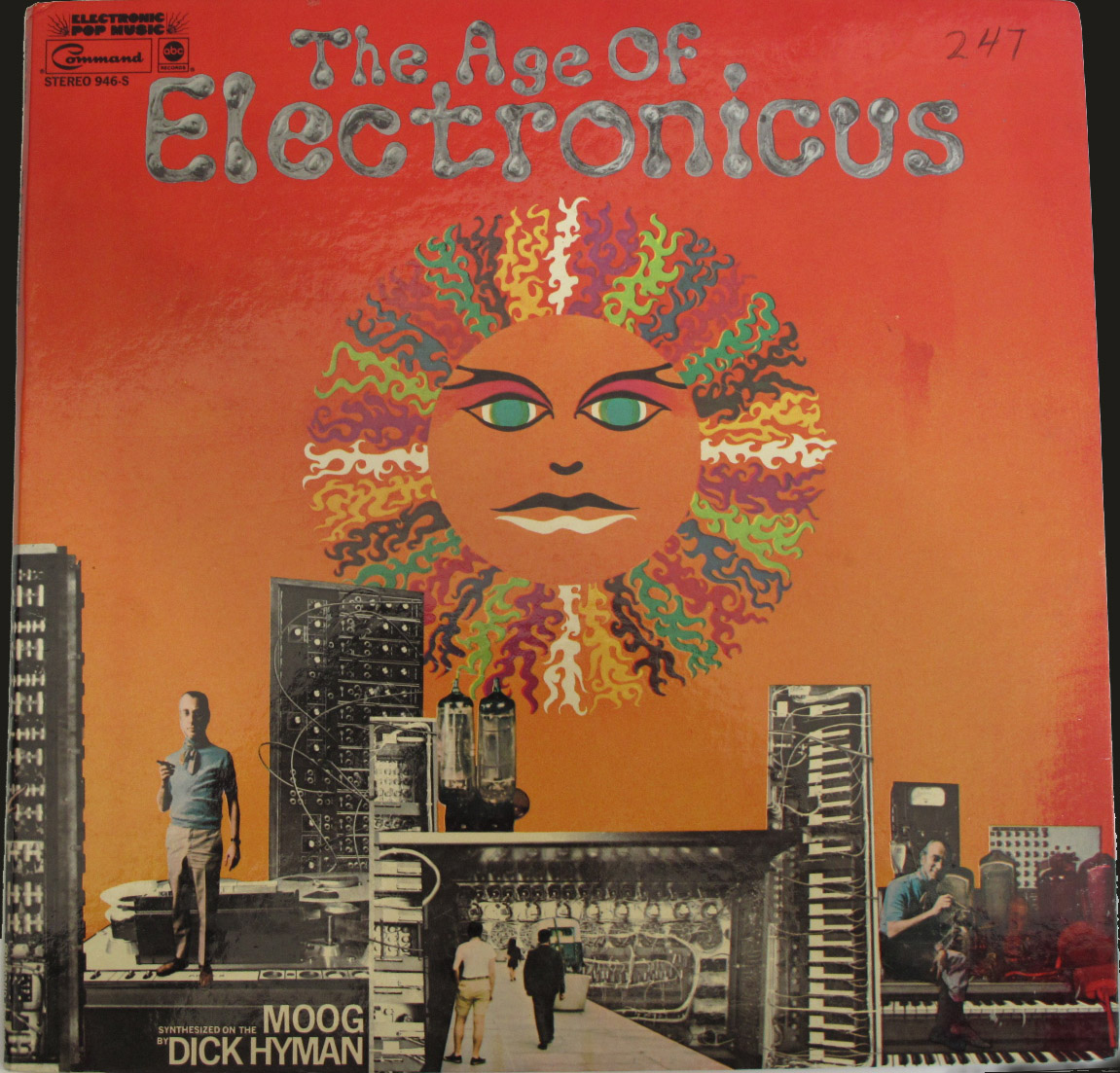

His mastery of Hammond and Lowrey organs also gave him insight into how to shape and play intriguing sounds with an electronic instrument. Hyman’s Moog immersion resulted in two full albums of Moogified jazz-pop, Moog: The Electric Eclectics of Dick Hyman (January 1969) and The Age of Electronicus (August 1969).

From the perspective of popular music history, Hyman’s Moog recordings were by no means the first. I’m aware of at least 45 recordings using the Moog Modular synthesizer released prior to Moog: The Electric Eclectics of Dick Hyman. However, as Wendy Carlos found with the release of Switched-On Bach only about a month earlier, listeners of the time were ready for electronic music that was more than sound effects and psychedelic sounds.

Interestingly, Hyman was working on his Eclectics album around the same time that Switched-On Bach was being released. Hardly a month later, in January of 1969, after reportedly spending 70 hours crafting the album in the studio, Command unleashed Hyman’s first LP of electronic jazz pop.

The accompanying advertisement clearly characterized what they had in mind. While the Carlos disc was for classical music buffs, Electric Eclectics was “Switched-on pop for ‘counter’ revolution!” i

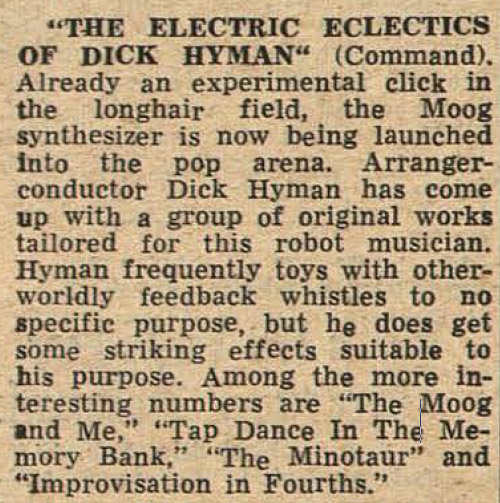

A brief review from Variety repeated the idea that Moog music was for everybody.

Hyman had the first chart-making single using a Moog synthesizer, “The Minotaur.” Six months later, in June 1969, Gershon Kingsley released an album called Music to Moog By that contained a little pop song called “Pop Corn.”

Although it wasn’t an instant hit in 1969, “Pop Corn” became a hit during the early 1970s for Kingsley and others. In the span of only six months, three of the most influential albums of highly tuneful electronic music had been released, inspired others, sold more synthesizers, and helped spawn a new industry in electronic music equipment.

These records by Carlos, Hyman, and Kingsley became the killer apps that made the future of electronic music possible.

How it was done

Hyman is primarily a musician, not an engineer, so for his Moog music he partnered with audio technician Walter Sear (1930-2010), Bob Moog’s New York sales and technical representative. Sear worked with Hyman by programming the Moog patches and engineering the multi-track recordings. Often Hyman would suggest a kind of sound and the two would explore patches until they found what they liked. ii

“All the recordings on the two albums were done in Walter’s studio,” explains Hyman, “which was in the penthouse of the Great Northern Hotel on 57th Street. I was experienced on the Wurlitzer, Hammond and Lowrey organs, and was able to relate many of the synthesizer’s possibilities to those keyboards. Walter would suggest registrations or tone productions which were new to me; sometimes I would ask him for settings comparable to my experience as an organist.” iii

Command instrumental recording sessions took place in the ballroom of the Great Northern Hotel, also known as Finesound because of Bob Fine, the recording engineer. Enoch Light produced, and Bobby Byrne and Loren Becker were his assistants.iv Moog tracks were mostly recorded separately in Walter Sear’s studio, and then, for certain tracks, mixed with prerecorded instrumental tracks.

Enoch Light produced several recordings featuring the Moog and other non-electronic instruments, including drums and brass. Dick Hyman played Moog and other keyboards on some of these, while other times Walter Sear played the Moog.

Hyman, working with Sear, approached each session as one of exploration. Some pieces were totally improvised in this fashion. When Sear had presented a new and intriguing sound, Hyman would work out a melody or pattern, and then build the piece on successive tracks. The “composition” per se was the multi-track recording itself, not a page of written music.

Other pieces were based on compositions by Hyman, newly created for the album, or in some cases older works re-arranged for the new tonal universe offered by the Moog modular. In Hyman’s second album, The Age of Electronicus, most of the tracks were arrangements based on then current recordings by other artists of the time, from The Beatles to James Brown.

The recordings

Hyman’s memories of making the two Moog albums are vivid. Electric Eclectics primarily consisted of original works composed using the iterative process just described. The Age of Electronicus consisted of cover versions of pop music of many styles, from songs by Booker T., Burt Bacharach, and Joni Mitchell to the most mind-blowing interpretation of James Brown’s “Give It Up or Turn It Loose” you’ll ever hear.

Some of the tracks include additional instruments, such as drums, organ and harpsichord. But the predominant sound on both albums — including many instrumental solos — was that of the Moog modular synthesizer.

Moog: The Electric Eclectics of Dick Hyman (LP, Command 938 S, January 1969)

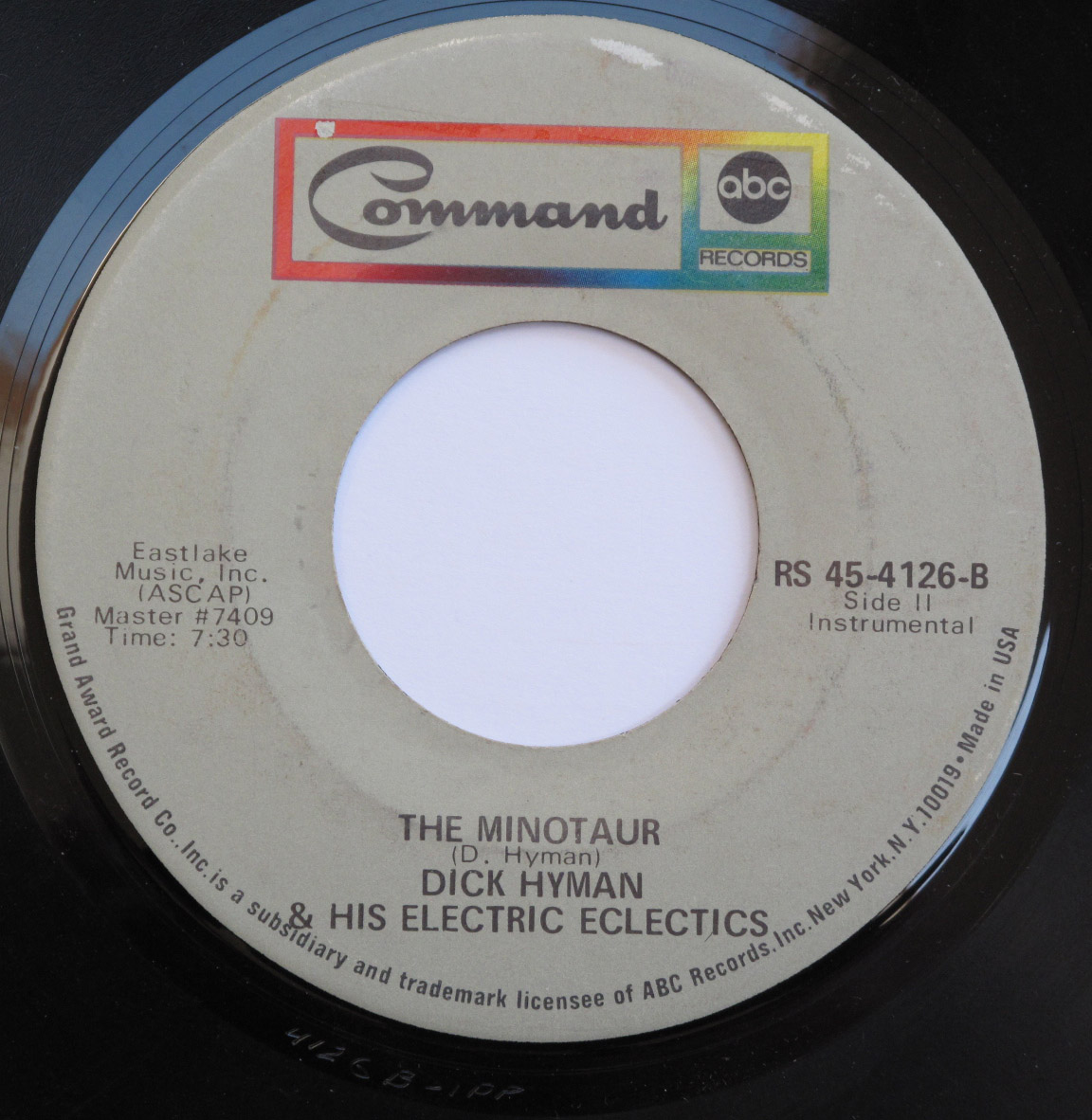

Dick explains that “The Minotaur” used a Maestro Rhythm Master drum machine. The Rhythm Master was an early drum box with ten settings for preset rhythms, such as Rock1, Rock2, Mambo, Cha Cha, Bossa Nova, Foxtrot, and others. To use it, you pushed a button and then controlled the tempo with a rotary dial.

“The Minotaur” was recorded as three improvised overdubs on top of a drum machine track, the three parts being the melody, bass line, and the raga-like drone tone. “The drum machine beat was an odd result of combining a waltz with a bossa nova. It was a lucky inspiration, all around.” v

“The Minotaur” was released as a 45 RPM single, but in two versions, the original 7:30 version from the album and a radio edit of 3:19. I remember hearing both on AM radio. As hit records go, it was a modest success. But when you consider that this electronic jazz number was competing for attention all year with the likes of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan, the Temptations, the Isley Brothers, James Brown, Glen Campbell, Dionne Warwick and a host of other pop stars in their prime, it’s clear that “The Minotaur” captured the imagination of the time.

Back in those days when everything was measured by chart success, “The Minotaur” finished the year at no. 38 on the Billboard Hot 100 and 27 on the Billboard R&B Singles charts. The album peaked at no. 4 on the Billboard Jazz charts and no. 30 on the Billboard 200.vi

What was most impressive about “The Minotaur,” however, was the totally audacious solo played with sliding tones across several octaves — a function of the Moog ribbon controller.

Anybody who later heard Keith Emerson’s ribbon controller solo in the hit “Lucky Man” couldn’t help but recognize the similarity to Hyman’s playing over a year earlier. I think it can be safely said that Hyman first established this sliding note style as a musical Moog technique.

“The glissandi effects I used, particularly on ‘Minotaur,’ Hyman said, “came about as a natural improvisation when I became aware of the potential of the slider. I don’t think I had heard any tone production like it before that time other than an air raid or fire siren.” vii

Hyman drew upon a variety of sources and styles for other tracks on the album, often adding other instruments to the mix. He explains that “‘Total Bells and Tony'” was an homage to the clarinetist Tony Scott, whom I had played with and arranged for some years prior. ‘Tap Dance in the Memory Banks,’ for which Walter must have shown me the tap dance potential of the Moog, after which a science fiction scenario emerged.

‘Four Duets in Odd Meter’ had been composed and published prior. ‘Evening Thoughts’ combined two previous compositions, which I pre-played on a Lowrey organ in the Finesound studio [in the ballroom]. Essentially, that was an organ performance to which we added synthesizer decorations, many suggested by Walter, I suspect. ‘Topless Dancers of Corfu’ and ‘The Legend of Johnny Pot’ were composed for the album and recorded with Bill LaVorgna (drums) and Chet Amsterdam (bass). I played Moog and honky-tonk upright piano with them.” i

All nine tracks on the album show off various characteristic of the Moog modular, from sweeping glissandi, percussive melodies, repeatable sequences, and delicate modulations of colorful tones. What impresses me the most about this album is that Hyman had the courage to let the Moog be the Moog, transforming its quirky tonalities and challenging programming into a new musical voice that was clearly the sound of Moog.

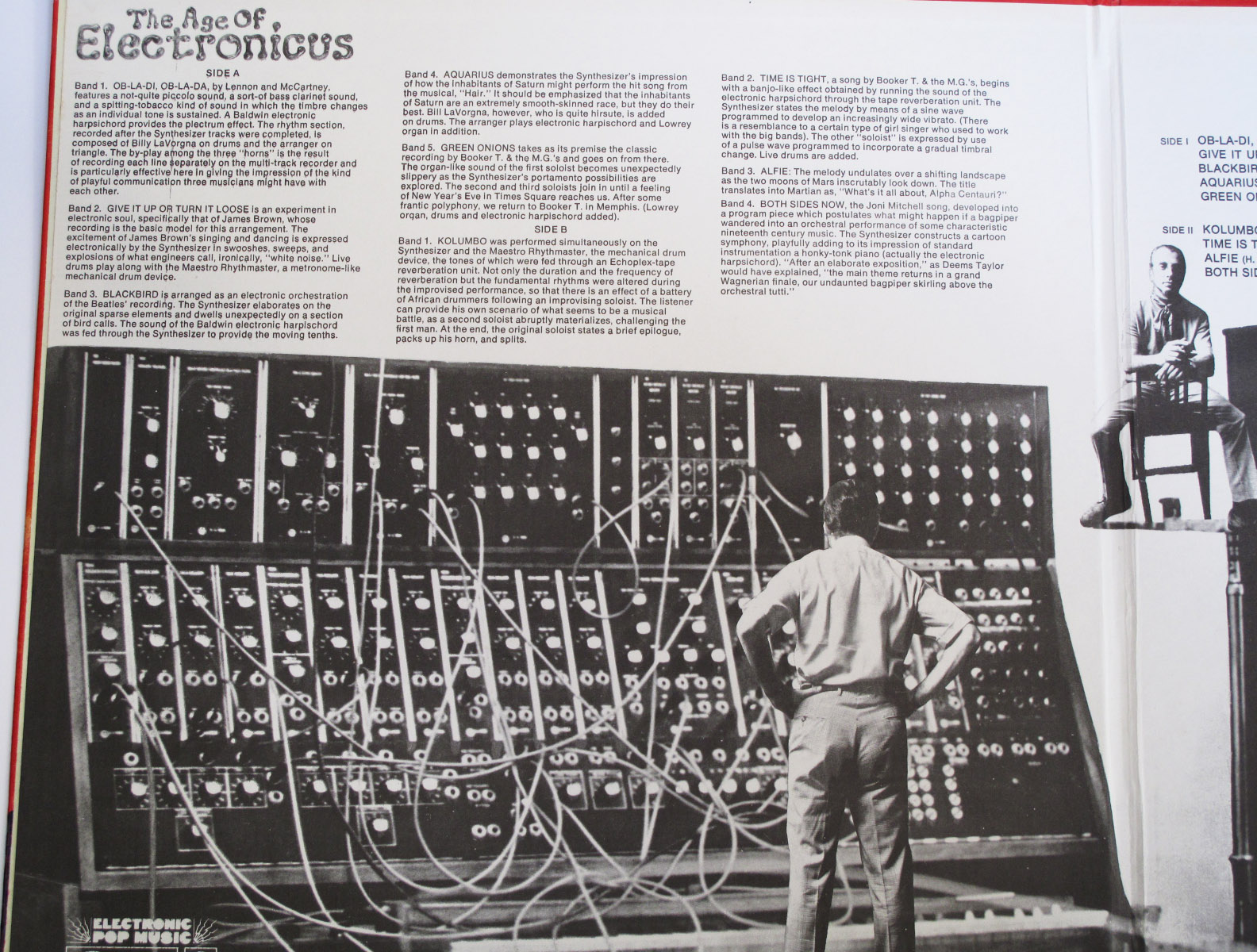

The Age of Electronicus (LP, Command 946 S, August 1969).

For his second all-Moog album, Hyman included mostly cover versions of hits from other artists. While many other artists had begun to get on the Moog bandwagon by doing the same, Hyman’s choices were distinct and his interpretations bold. Of the nine tracks on The Age of Electronicus, only one was a Hyman original: “Kolumbo.”

“Kolumbo” was an improvisation using looped synthesizer percussion as well as the Maestro, fed through an Echoplex-tape unit with reverb. It’s the most experimental jazz of the tracks on this album.

Not mentioned in the album liner notes are Bill LaVorgna’s long drum solo, which was the root of “Give It Up or Turn It Loose”; Bill’s drums and Chet Amsterdam’s bass on several other tracks, as well as the Baldwin electric harpsichord.”

Hyman’s favorite track on The Age of Electronicus? “For me,” says Hyman, “the most satisfying though peculiar arrangement is my from-bagpipes-to-Bach approach on ‘Both Sides Now.'” ii

Although Hyman played the Moog Modular on select tracks on some other albums, these two LPs form 1969 form the canon of his most influential Moog modular work. He also programmed the Moog himself for some more obscure releases that I would like to explore in a future blog.

After his experience with the Moog Modular, Hyman also became a Minimoog player, recording on several tracks for a variety of artists. I mention this because I think his Minimoog solo on the Bill Watrous jazz track “Ayo” (1974, from Manhattan Wildlife Refuge) ranks up there with Don Preston’s Minimoog solo on Zappa’s “Waka/Jawaka” (1972, from Waka/Jawaka) as one of hippest of all time.

****

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog modular synthesizer.

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog modular synthesizer.

Twitter: @Thom_Holmes

blog: Noise and Notations

Twitter: @Thom_Holmes

blog: Noise and Notations

If you want to read more from Thom Holmes, please see his many fascinating historical blogs here: http://moogfoundation.

i Command Advertisement. Billboard, Feb 15, 1969: 73.

ii Myers, Marc. Interview with Dick Hyman. JazzWax. January 6, 2010. http://www.JazzWax.com/2010/01/interview-dick-hyman-part-3.html

iii Hyman, Dick. Correspondence with Thom Holmes. April 12, 2014.

iv Settino, Curtis. Dick Hyman. Tape Op, November 15, 2012. http://www.tapeop.com/interviews/92/dick-hyman/ ; Hyman, Dick. Correspondence with Thom Holmes. April 12, 2014.

v Settino, Curtis. Dick Hyman. Tape Op, November 15, 2012. http://www.tapeop.com/interviews/92/dick-hyman/

vi http://www.columbia.edu/cu/alumni/Magazine/Fall2006/hyman.html; Billboard, http://www.allmusic.com/album/moog-the-electric-eclectics-of-dick-hyman-r66978/charts-awards/billboard-single

vii Hyman, Dick. Correspondence with Thom Holmes. April 12, 2014.

viii Hyman, Dick. Correspondence with Thom Holmes. April 12, 2014.

ix Hyman, Dick. Correspondence with Thom Holmes. April 12, 2014.

I have both of the Hyman Moog albums and still play them from time to time. I used to play them both on my college radio show in the 70s and people always called me to ask what the **** is that? I love them both to this day.

I bought Age of Electronic us, and the other orange cover lap by DickHyman many years ago. Like it a lot, lost both moving many times. Like to get a download of his music, any ideas of availability ?

Thanks for your interest in Dick Hyman’s Moog music. I am not aware of a digital download for either of the Hyman Moog LPs, e.g., on iTunes or Amazon. But both have been available on CD. Check out Amazon or even eBay for that.

Unfortunately, “Dick Hyman – The Age of Electronicus” isn’t listed as available on audio CD or as ever having been released on audio CD (at least as of May 2015)

“Dick Hyman – Moog – The Eclectric Eclectics Of Dick Hyman”, and two tracks from “The Age of Electronicus” appear to now be available, as bonus tracks on the CD “Dick Hyman / Mary Mayo – Moon Gas” (OMNI – 180)

Film/broadcasting sense is 1914.

One other comment. Emerson played part of The Minotaur as part of a live solo during “Come Take A Pebble” on one of their live albums. A very nice homage, that’s for sure.