Jazz Embraces the Moog Synthesizer

By Thom Holmes

Jazz was one of the last major genres of music to embrace the synthesizer. What made it possible for synthesizers to finally thrive in jazz was portability: the availability of portable performance instruments such as the Minimoog and Arp 2500 in 1970. Only then, did the synthesizer effectively adapt to the needs of live performance and improvisation that are at the heart of jazz. With the introduction of the Minimoog and a host of other portable electronic instruments, the synthesizer quickly became a staple of contemporary jazz in the 1970s.

Before the Minimoog, however, a small number of visionary jazz musicians found ways to use the Moog modular synthesizer in a jazz setting. This month, I want to take a look at some of their work.

Most of the time, using a Moog Modular in jazz meant overdubbing Moog tracks to accompany jazz instrumental tracks recorded earlier. In at least one case, that of Musica Elettronica Viva, a Moog Modular was taken on the road for dozens of free improvised performances.

Herb Deutsch, the first Moog jazz composer

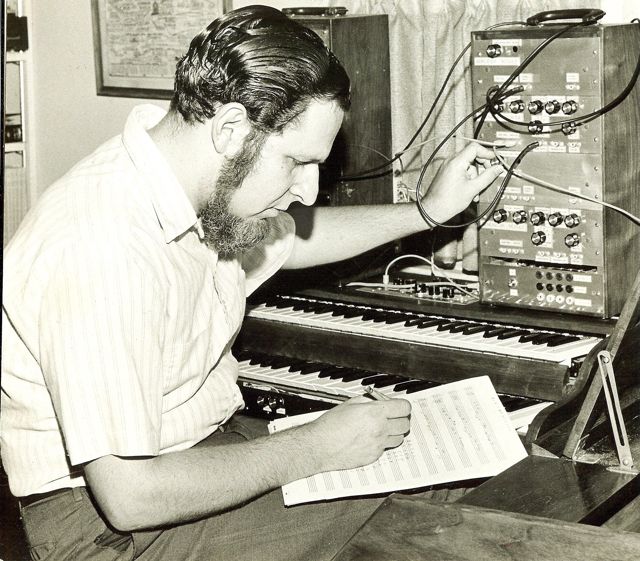

The story of Bob Moog’s collaboration with composer and music educator Herb Deutsch is well known. Together, they collaborated on the development of the first Moog modular synthesizer prototype, completed in August 1964. Herb influenced the decision to add a keyboard controller to the synthesizer. In the fall of 1964, Deutsch composed Jazz Images: A Worksong and Blues, the first musical composition to incorporate a Moog Modular Synthesizer.[i]

The work was written for piano, Moog, taped sounds, and jazz combo. The 10-minute recorded piece featured everything from a bluesy melody played on the monophonic Moog, to a dialog between piano and Moog, and the interplay between horns, a rhythm section and electronic sounds on tape. A landmark at the time, not many people heard the work because it was never released on record.

Thankfully, a recording is now available from Ravello Records.

Bob Moog, Herb Deutsch, and an unknown announcer at the “Jazz in the Garden” concert at MOMA, August 28, 1969

Deutsch continued to work with Bob, and eventually the two put together a historic concert at the Museum of Modern Art in New York on August 28, 1969. For this concert, they used four Moog modular synthesizers in a live setting. This program was also jazz-oriented, and was given the title, “Jazz in the Garden.” The live concert featured a Moog quartet with Deutsch on monophonic lead Moog, Hank Jones at a dual keyboard setup (one Moog, the other an electric piano), Artie Doolittle on modular bass synthesizer, and Jim Pirone on modular percussion synthesizer. Bob Moog prepped all of the instruments and served as engineer for the concert.[ii]

Other jazz experimenters

Interest in using the Moog Modular in jazz resulted in several interesting experiments between 1967 and 1970. Here is an overview of several for which there are recordings.

Musica Elettronic Viva (MEV)

Live Electronic Music Improvised (Mainstream MS/5002, US, 1968)

Musica Elettronic Viva (Polydor 583 769, UK, 1969)

The Sound Pool (Byg Actuel 26, 529.326, France, 1969)

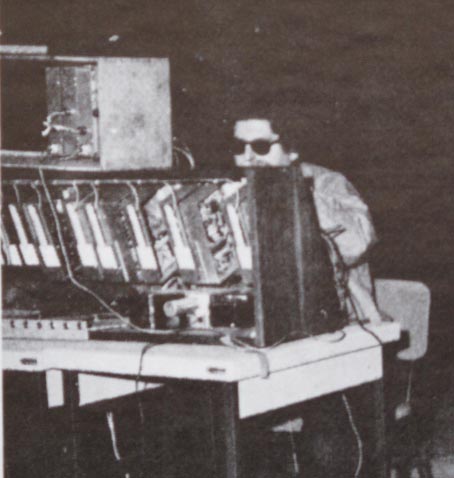

The earliest and boldest use of the Moog in jazz was the work of Richard Teitelbaum, an American composer and co-founder of the free improvisation ensemble Musica Elettronica Viva (MEV). Based in Italy, the original lineup of MEV included Alan Bryant (electronics), Alvin Curran (piano, trumpet, voice), Frederic Rzewski (electronics), Ivan Vandor (saxophone), and Teitelbaum (Moog and biofeedback processing). Teitelbaum was the first person to bring a Moog Modular to Europe and was a pioneer in the use of amplified brainwaves for musical purposes.

The earliest and boldest use of the Moog in jazz was the work of Richard Teitelbaum, an American composer and co-founder of the free improvisation ensemble Musica Elettronica Viva (MEV). Based in Italy, the original lineup of MEV included Alan Bryant (electronics), Alvin Curran (piano, trumpet, voice), Frederic Rzewski (electronics), Ivan Vandor (saxophone), and Teitelbaum (Moog and biofeedback processing). Teitelbaum was the first person to bring a Moog Modular to Europe and was a pioneer in the use of amplified brainwaves for musical purposes.

Teitelbaum befriended Bob Moog in 1966 and engaged the inventor’s help in finding a way to amplify brainwaves so that they could be processed as electronic sound. Bob made for him a low-cost, high-gain differential amplifier, and in the fall of 1967, Teitelbaum made the down payment on a used Moog synthesizer and returned to Europe with this equipment to rejoin MEV.[iii] There, MEV performed hundreds of concerts over a three-year period, often using Teitelbaum’s biofeedback circuitry to process amplified brainwaves using the Moog modular. Members of the audience frequently participated in the performances. The tracks found on these three albums capture such shows. This is jazz improvisation at its freest, exploring remarkable textures, noise, and interaction between acoustic and electronic instruments.

Burton Greene

Presenting Burton Greene (Columbia CS 9784, recorded in New York, 1970)

Burton Greene’s 1970 recording is outstanding in many respects. Greene is a free jazz artist who also worked at the time in modal styles, combining ideas from Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor with those of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. He had already completed the recording sessions with his quintet for this LP when producer John Hammond asked Greene if he would like to add some Moog modular sounds to the record. Greene later remarked that although this seemed like an odd idea at the time, they offered him an additional $500 to sit down with Moog representative Walter Sear and create the electronic sounds.

Burton Greene’s 1970 recording is outstanding in many respects. Greene is a free jazz artist who also worked at the time in modal styles, combining ideas from Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor with those of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. He had already completed the recording sessions with his quintet for this LP when producer John Hammond asked Greene if he would like to add some Moog modular sounds to the record. Greene later remarked that although this seemed like an odd idea at the time, they offered him an additional $500 to sit down with Moog representative Walter Sear and create the electronic sounds.

Greene had actually met Bob and Shirleigh Moog in 1963 and knew about the synthesizer, but relied on Sear’s expert programming to create the patches needed for his overdubs.[iv] On this record, the Moog is only evident on the wonderful free jazz track, “Slurp,” intermixing perfectly with the improvised noise beats and tones of the quintet. This is a fantastic and long-forgotten recording of free jazz during the formative period when electronic instrumentation was taking many musicians in the direction of fusion jazz.

Don Sebesky

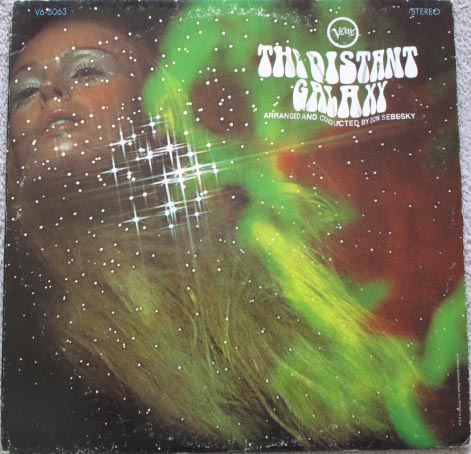

The Distant Galaxy (Verve V-65063, December 1968)

Don Sebesky is a GRAMMY Award-winning trombonist and arranger, whose many credits include music for theater, television, popular song, and jazz. The Distant Galaxy was his second album as a leader and featured big band arrangements of several popular songs plus some original compositions. The spacey attitude of the production is evident from the cover art to the seven brief electronic interludes that he created with the Moog modular and inserted between the longer tracks on the album. Famed Command artist Dick Hyman, known later for his own Moog records, is a featured pianist along with a broad selection of jazz instrumentalists.

Don Sebesky is a GRAMMY Award-winning trombonist and arranger, whose many credits include music for theater, television, popular song, and jazz. The Distant Galaxy was his second album as a leader and featured big band arrangements of several popular songs plus some original compositions. The spacey attitude of the production is evident from the cover art to the seven brief electronic interludes that he created with the Moog modular and inserted between the longer tracks on the album. Famed Command artist Dick Hyman, known later for his own Moog records, is a featured pianist along with a broad selection of jazz instrumentalists.

Sebesky himself is credited with the Moog modular sounds and Rick Horton with additional electronic effects. As timing goes, this work was an early example of funky jazz-rock with electronics. In addition to the short interludes, two full tracks feature the Moog. “Soul Lady” (also with Dick Hyman on piano) has a nice Moog break and duet with Hyman. On “Water Brother,” the Moog is played fluidly using a ribbon controller, contributing many textures, breaks, and exchanges with flutist Hubert Laws and clavinet player Warren Bernhardt. The Moog in this case sounds very much like a theremin.

Bobby Byrne

Shades of Brass (Evolution 3003, March 15, 1969)

This is Robert Byrne’s second LP of Moog covers for Evolution Records and is more jazz-like than his earlier collection of hits from the Broadway musical Hair (Electric Hair: Switched-On Hits from America’s First Tribal Love Rock Musical, Evolution Records 2013).

This is Robert Byrne’s second LP of Moog covers for Evolution Records and is more jazz-like than his earlier collection of hits from the Broadway musical Hair (Electric Hair: Switched-On Hits from America’s First Tribal Love Rock Musical, Evolution Records 2013).

This record is a funky exploration of popular songs by the likes of Burt Bacharach, Simon and Garfunkel, and others. Dick Hyman, Byrne, Walter Levinsky, Richard Lieb, and Chico O. Farrill did the arrangements. Byrne was associated with Command Records and Enoch Light during the 1960s as an arranger and producer. This music is dominated by brass and proves to be an interesting experiment in blending the Moog modular with driving jazz arrangements. There are Moog bass solos, melodies, sound effects, and textures aplenty, often having the feeling of a soundtrack for an action film. In particular, the Moog solo on “Help Yourself” is an outstanding example of the rising and falling notes created by a Moog portamento controller, and there is a fun duet between sax and Moog on Aretha Franklin’s “Respect.”

Enter the Minimoog

R. A. Moog and Co. introduced the Minimoog in early 1970. This would be the instrument that jazz and rock players would soon adopt for their live performances. But it took some months before sales of the Minimoog took off, peaking by the middle of 1971. One of the first musicians to adopt the Minimoog happened to be jazz great Sun Ra. This is an interesting story that began with a visit to Bob Moog’s plant in the fall of 1969. We’ll explore this important jazz moment in an upcoming blog entry.

To read the first installment of this blog series exploring how technology and musical artistry influence one another, click here.

To read the second installment of this blog series with the first 10 recordings using a Moog, click here.

To read the third installment of this blog series exploring recordings that are often thought of as using Moogs, but do not, click here.

***All images provided by Thom Holmes except those featuring Bob Moog and Herb Deutsch.

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

Thom Holmes is a music historian and composer specializing in the history of electronic music and recordings. He is the author of the textbook, Electronic and Experimental Music (fourth edition, Routledge 2012) and writes the blog, Noise and Notations. For his ongoing project, The Sound of Moog, he is archiving every known early recording of the Moog Modular Synthesizer.

If you want to read more from Thom Holmes, please see his many fascinating historical blogs here: http://moogfoundation.

[i] Deutsch, personal correspondence, February 14, 2012.

[ii] Stanleigh, Bertram, Moog Jazz in the Garden, Audio Magazine, November 1969, p. 96

[iii] Teitelbaum, Richard. In Tune: Some Early Experiments in Biofeedback Music. Biofeedback and the Arts: Some Results of Early Experiments, David Rosenboom, editor: Aesthetic Research Center,. Vancouver, British Columbia, MIT Press, 1976, pp. 35-56.

[iv] Interview with Burton Greene. http://www.paristransatlantic.com/magazine/interviews/greene.html

Do you consider the 2 Moog albums by Dick Hyman as early jazz workings? The Minataur was a pop tune, but there were a lot of interesting tunes on both of those LPs.